Its been relatively quiet down at the apiary over the winter months with the bees mostly staying in their hives even if they did not cluster for long periods due to the warm weather we experienced again in the south east.

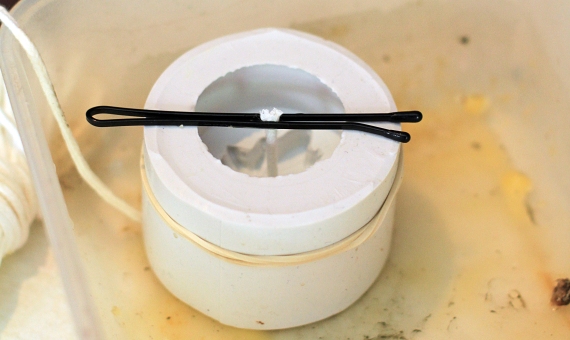

I did not feed any syrup in August following the honey removal last year as it was such a good year that the bees were still bringing in pollen and nectar late into the season and I had left a good amount of honey on the hives as this has to be better for them than a sugar substitute! I checked back on the bees around new year when I also applied oxalic acid, dribbled between the frames to help control the mite whilst the colony was without sealed brood, and gave each hive some bee candy above the crown board as an insurance policy against starvation. Its always nice to see the girls doing well at this stage but I am quite aware that this is never a guaranteed sign that they will all make it into spring.

The bees were still quite active and a few followed me when I left the apiary which was sad knowing that these would soon chill and fail to find their way back home….

My bee buddy Paul and I also moved the apiary to a new location around new year, it was only a few hundred meters across the land so that the bees will now get more light earlier in the day as they had become overshadowed by the tress rapidly filling the skyline around their old homestead. Winter is one of the few times you can move the hives like this, at other times you have to stick to the ‘less than 3 feet or more than 3 miles’ rule to prevent the bees returning to the original hive location and clustering on the ground.

We strapped the hives but didn’t block the entrances and wheeled them carefully across the bumpy ground in a wheelbarrow. All the bees behaved and stayed indoors until we got to the final hive with the feisty black British queen (these are my best honey makers) and they came streaming out en-mass and found a hole in Paul’s gloves to let him know about their disapproval, needless to say I ended up moving that one on my own.

I returned to lift the roofs and check how the bees were getting on in February and a couple of hives had started to nibble the candy, despite still having some honey in the outside frames, just goes to show that they would rather go up than sideways in their search for supplies.

Early April saw a mini heatwave across the UK with above average temperatures and sunshine hours and the bees didn’t waste a minute of it. The bees have been very busy and nearly all the hives had 8 or 9 frames of brood and pollen across the ‘brood and half’ system that I run. With colonies this strong it was definitely time to add the first supers to give the bees more room for stores, prevent hive congestion and maybe delay the inevitable swarming for a couple more weeks whilst I get my backup gear sorted and ready for use.

As a beekeeper with a busy life, young family and full time employment I don’t often get the opportunity to simply stand back and watch the bees but I recently took some time to photograph the bees activity at the apiary and just enjoy watching them in flight bringing in the spring pollen, you can learn so much about the strength and health of a colony through observation at the entrance and its far less intrusive to the bees than opening the hive up. I hope to get the time to do this a bit more often in the future….

The weather has become more unsettled, with cooler wet and windy weather across the UK this week and the girls are not flying as much but I have no doubt that they are still just as busy indoors and planning the plot to their own ‘game of thrones’ so now I am just waiting for a break in the rain to try and catch up with them….

As ever I will be adding to this blog as and when time allows and I am not actually elsewhere or with the bees in 2015, thank you for taking the time to read my ramblings and for your continuing comments and questions – this makes it all worth while for me as the writer….

I can also be found at @danieljmarsh on twitter or British Beekeepers page on Facebook.